Counting Cherry Stones: the White Feather Wielder and the Down-trodden Woman

I tried writing about them separately. They wouldn’t have it. No sooner did I get to describing one of them and there was the other, beating the door down, getting her feet under the table, shaking her head, rolling her eyes and saying “You think you’re going to write about her and leave me out of it?”.

I tried writing about them separately. They wouldn’t have it. No sooner did I get to describing one of them and there was the other, beating the door down, getting her feet under the table, shaking her head, rolling her eyes and saying “You think you’re going to write about her and leave me out of it?”. I looked at them – unreal though they are – and they looked alike. Are you one and the same then? I thought. Through one eye they are almost impossible to tell apart; through the other one would never have thought them related. Not identical then, but not easily separable.

They are the two heads to the same coin. Mirror images. Inversions. When one’s down the other’s up. Janus looking forward and back. Two-faced.

Like Rosie, the white-feather wielder casts her echoes before her, flowers strewn before the troops departing for battle. Once she was a Spartan mother sternly instructing her son, “Come home with your shield or on it.”

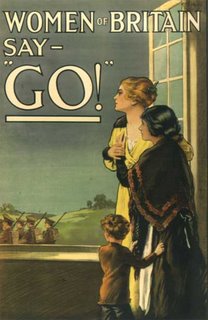

Ninety years ago or thereabouts, she strolled through these streets, cool and slim in long Edwardian skirts, white feather held jauntily between thumb and forefinger seeking out unmilitary men. Men to chastise for their ununiformed unmanliness, for above all she is a womanly woman.

The white-feather wielder is man-made and in that she is the same as many womanly women. Rosie also sprang fully-formed from the forehead of J. Howard Miller, a latter-day Athena for an industrial age. She too had her avatars and her priestesses to officiate at her altar poised precariously on the fuselage. Is the white-feather wielder also a goddess then? Or is she a demon, this womanly woman? Lamia. Seductress. Despatching young men to drown in mud, just as the sirens sang them down beneath the swell. Her creator described her and her gift as “far more terrible than anything they [men] can meet in battle.” Perhaps to those who believed in ideas of manliness and womanliness she was more terrible at that.

Unlike Rosie, the white-feather wielder has not gathered a stable iconography about herself. She has not become a symbol of women’s liberation or power. She did exercise a particular kind of power though, using her words to persuade men to go and slaughter or be slaughtered. Perhaps the War Poets caught her off-guard: some of them took a dim view of drowning in mud and a dimmer view still of the particular form of manliness which she upheld. In any case revival efforts in World War II failed dismally. She had come to be seen as a woman who used her feminine wiles to send young men to their deaths. A Lorelei repeating endlessly the old lie: Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori.

Like the leopard, she had to change her spots. Scatter her feathers to the four winds. Feathers? What feathers. No feathers here. These days, she’s a ‘security mom.’ For a while before that she was a soccer mom: she still is. Clad in jeans and sneakers, slightly harried, ferrying the kids to practice in the SUV with the the red-white-and-blue festooned bumper and the yellow ribbon (faded now from a couple of years of sun, rain and snow) drooping from the antenna. She’s all for staying the course: after all the troops are protecting her children from terrorism. And if that means recruiters in schools – well that’s what it means and that’s all there is to it. It’s like the man on the T.V. said “We’re fighting them over there so we don’t have to fight them over here.”

“And after all, look how they treat the women!” she says. “Just barbaric.”

The coin spins on its edge and comes down heads.

Sometimes she’s Belgian. Perhaps she’s a nun in a torn habit. More recently she’s been spotted in a chador. But she has worn many different kinds of clothing in her myriad lifetimes, she has lived in many different places. Once she may have been a kidnapped bride. Did she stand atop Troy’s towers? Perhaps so, but now she has been safely reduced and diminished so that the one central fact of her life, the sine qua non of her existence is her oppression. She is dust beneath the enemy’s heel, foreign or domestic: bereft of agency or resistance. She has no avatars, only involuntary sacrifices. What woman would choose to embody her?

Like the others – the Grocer’s Daughters, the Rosies, the White-Feather Wielders, the Down-Trodden woman is a type, a figure, used in service of war-making. Which is not to say women are not often oppressed, or even to debate which forms of oppression are to be considered culturally superior. That is not the point. The point is that the Down-trodden Woman, whoever she is and whereever she comes from, needs liberating and we know just the folks for the job. Results guaranteed.

Like the others – the Grocer’s Daughters, the Rosies, the White-Feather Wielders, the Down-Trodden woman is a type, a figure, used in service of war-making. Which is not to say women are not often oppressed, or even to debate which forms of oppression are to be considered culturally superior. That is not the point. The point is that the Down-trodden Woman, whoever she is and whereever she comes from, needs liberating and we know just the folks for the job. Results guaranteed.

She is a strange creature, this Down-trodden Woman. So clearly visible in the Enemy’s citadels, yet when the citadel is stormed she evaporates like a puddle on a hot day. Her liberation is so instantaneous it leaves no trace. Practical indicators of her presence– the number of women being raped, for example – may increase quite dramatically. And certainly it is true that after liberation, actual women may also have far less in the way of practical opportunities to keep themselves from such things as starvation. All of which might suggest that the Down-trodden Woman should still be there, that she had no business leaving yet, but no. She has gone her ways. She vanished the moment the first ‘liberator’ passed through the gate.

To complain about such practical indicators – to gripe and moan, to whine and wail, to bitch – is simply to mistake the nature of the Down-trodden Woman’s Liberation. It is symbolic. Or perhaps more accurately, it is nominal, pertaining to names. The Down-trodden Woman is Liberated because certain generous gestures have been made. Certain phrases have been pronounced correctly. Incantations recited over just the right bubbling stew.

The lives and living conditions of actual women have absolutely nothing to do with the Down-trodden Woman’s Liberation: they never did.